Deal with it

Esthétiques de la réparation

Research project

Ongoing

support programme by

CARE et photographie: Que peut une image ? Esthétique de la réparation

Monday 21 november 2022

lecture, La Cambre, Bruxelles (BE)

CARE et photographie: workshop with Anna Püschel

Monday 21 and Tuesday 22 november 2022

workshop, La Cambre, Bruxelles (BE)

Photographic Practices as Care-Taking:The Pharmakon Image

Thursday 24 and Friday 25 november 2022

paper presentation, UiT Arctic University of Norway, Tromsø (NO)

Itinéraires de réparation: moss in conversation with Estefanía Peñafiel Loaiza

Wednesday 14 december 2022

lecture, Beaux-Arts de Paris (FR)

Workshop with Hideyuki Ishibashi

Tuesday 24 january 2023

workshop, Lycée Professionnel Louise de Bettignies, Cambrai (FR)

moss collective and Livia Melzi in conversation with Béatrice Josse

Thursday 25 may 2023

lecture, Institut pour la photographie, Lille (FR)

Considering images both as bearers of different forms of real or symbolic violence and as interfaces for individual or collective repair, Deal with it – Esthétique de la réparation examines the curative aspect inherent in certain visual arts gestures in artistic practices, which act as tools of resistance. Erasure, covering, repetition, cropping, glitch, collection, imprint, collage, and even reconstitution, the multiple actions carried out by the artists on the body of images resemble attempts at conjuration and appropriation.

Physical or dematerialised, images can be personal, found, from archives, or amateur images circulating online. These distinct gestures then act as micro-actions of individual resistance to events and general media overload. Also participating in a recovery/showcasing of parallel images or narratives, they contribute to repairing a form of cultural forgetting and erasure, in order to change dominant narratives and representations.

As Legacy Russell points out in her book Glitch Feminism, ‘remixing (…) is a technology of survival’. Through close dialogue with a selection of artists who consider and heal images, this research project studies these different processes of resistance via images, within which the latter act as a pharmakon, both remedy and poison.

RESEARCH PLATFORM

Explore resources gathered over this research through the categories and tags below.{Resources}

RESEARCH PLATFORM

Explore resources gathered over this research through the categories and tags below.{Rendez-vous}

RESEARCH PLATFORM

Explore resources gathered over this research through the categories and tags below.{Research Process}

RESEARCH PLATFORM

Explore resources gathered over this research through the categories and tags below.︎ Repair ︎

RESEARCH PLATFORM

Explore resources gathered over this research through the categories and tags below.︎ Reconstruction ︎

RESEARCH PLATFORM

Explore resources gathered over this research through the categories and tags below.Five questions about care and resistance: Mika Sperling

How would you define care in your practice?

For I Have Done Nothing Wrong, prevention was definitely a topic for me. I discussed this with my husband: how do we prevent abuse from happening again ? How can we prevent having a blind spot? You think you’re doing everything, but then there is this blindspot, this one person you trust… So I thought, “it’s not all about control, you can’t always mistrust everybody”. I don’t want to live a life like this. But what I can do is to make an environment where my daughter trusts me, where she can tell me everything that doesn’t feel good. So that she won’t be afraid of making me sad. In a way, it sounds ridiculous, but this is exactly what happens: the children also protect us.

I feel like by doing I Have Done Nothing Wrong, I saved myself. I almost became like another person that offered a third perspective: I didn’t do this, someone else did this. I felt loved so much. I never knew what self-love is. Where is this love coming from? Yes, it’s coming from the people that see my art as well, but initially, it’s coming from myself. That is incredible. If I would’ve known how powerful this love is, I would’ve started much earlier doing the things that are good for me.

How would you define resistance in the context of your practice?

Considering I Have Done Nothing Wrong, I resist the urge to please my mother. She wasn’t pleased that I was publishing this, she was ashamed of being a bad person in this story - because she didn’t notice. So she is not portrayed in a good light. This makes me angry in a way -not at her specifically, but again the adult wants the story to be about them. But really, the story is about me and the abuser, it’s our story. It makes me angry that she’s sad about it. I resist to please her, because I feel by pleasing her, I’m dismissing myself again.

Do you see an intersection between gestures of care and gestures of resistance in your practice?

I just want to live a happy life. By confronting the transgenerational trauma, I feel we’re healing, as a family. I’m healing. There is just so much, I keep digging and there’s more and more and it’s never-ending. For example, there is a lot of shame in my family about lying: it’s the worst thing you can do, to lie. But don’t you want to know why people lie? Why do we sometimes feel forced to lie? So I’m interested in exploring that. I want to tidy up, to clean this whole mess. I want to become a better parent, a better mother, so I focus on all of this. My oldest daughter is now capable of lying, so when she lies, I’m just showing curiosity. I try not to judge her for it.

So when I think of care and resisting together, I think of resisting the old path. It is so much work to constantly reflect, but I do this almost on a daily basis. I’m sure a lot of parents can relate. You always want to make sure that you’re not blindly following a path. I constantly reflect to make sure I’m not destroying my child’s childhood. But this is exhausting at the same time. My daily life, my family life, is the source of my practice, and can be the start of a new project.

What is the role and power of images in your process?

I don’t always know what I want to say with my images, they just happen. I take them, and then later I look at them again, and then eventually my thoughts arrive at a certain point where it’s all there. The meaning of an image becomes clear, and I can give it a title.

So if you take for example Afraid To Fail You. In this picture of my daughter, she is sleeping and very vulnerable at that moment. And I see how thin her eyelids are, I see how blue the little veins underneath are, she has a little scratch on her forehead and all I can think is: “I’m afraid to fail you”. My images have little stories to them. Sometimes it takes a while looking at an image until I realize what it meant.This doesn’t happen overnight, I just go out and take the pictures, and see what they tell me.

Afraid to fail you, 660m away

Is resisting images through images possible?

I mean, the nightmares have stopped… I had this curve where things got worse during the project. I started and then it got a lot worse. There were these images popping up that never really happened, combined with documentaries that I watched - the ones about Michael Jackson and Woody Allen, the books I read by Vanessa Springora and Camille Kouchner... This all got mixed up in my head, creating these nightmares. So I thought that I made it worse. I think it was probably not so good for me to watch all of these in one month.

However, I wanted to meet my allies, and I realized we have so much in common. I felt what they were saying in these documentaries is so true to me. So I made it worse before it would get better.

When others are looking at the images I share, and telling me what they think, this is liberating to me. It gives the idea that I can take someone on a walk with me. I did this project all by myself, and no one knew except my husband. And now, people know my story, and they’re with me, I’m not alone. So I think the sharing part is the most healing too.

︎ Visit Mika’s website: mikasperling.de/home/i-have-done-nothing-wrong

With you, 55m away

Lívia Melzi on care & resistance in her practice

“ I like Nicholas Mirzoeff's concept of counter-visuality. Mirzoeff talks about visual tactics that allow us to question the dominant visual order. Like him, I do not believe that domination is absolute, and I find that photography is a wonderful tool to talk about power, especially through non-frontal gestures. I prefer discreet gestures.

The idea of resistance in my work perhaps applies to images that are constructed to be one single story, which - in turn - resists within our subjectivity. Images are not naive, and for me, there is an act of resistance every time I ask myself, in front of an archive: how, why, who? I think it is not me who resists, but the images themselves that are inexhaustible.

Perhaps there is a process of personal healing in revisiting images from the colonial era, in thinking about how Brazilian identity was constructed. It is an intimate path as well, because I always wonder which side I am on, how I position myself towards certain images.”

︎ More about Lívia’s work on her website: www.iviamelzi.com

Six questions about care and resistance: Léa Belooussovitch

How would you define the notion of care in the context of your practice?

In my practice, I would say that the notion of care could be related equally to materials, subjects and plastic gestures. Textile is very present in my work, as a support to receive textual sources or images: I often employ non-woven textiles (felt, mops, single-use cloths, etc.) which have strong capacities of absorption for matter and sound. I see it a bit like a bandage, blotting paper that soak up a vulnerability or an injury.

Also by means of cropping and reframing existing images, by eliminating areas of the image, it is as if the image were purified and therefore “cured”; often in my works, we don't see anything directly violent, the violence is located offscreen, in a text or in the abstract content, in a way this is also a form of visual care.

The subjects that I address, such as the last wishes of prisoners sentenced to death, the wives of accused criminals, or animals mistreated by men, are innocent witnesses of a tainted humanity, and offering them the central stage in my work is my way of taking care of them.

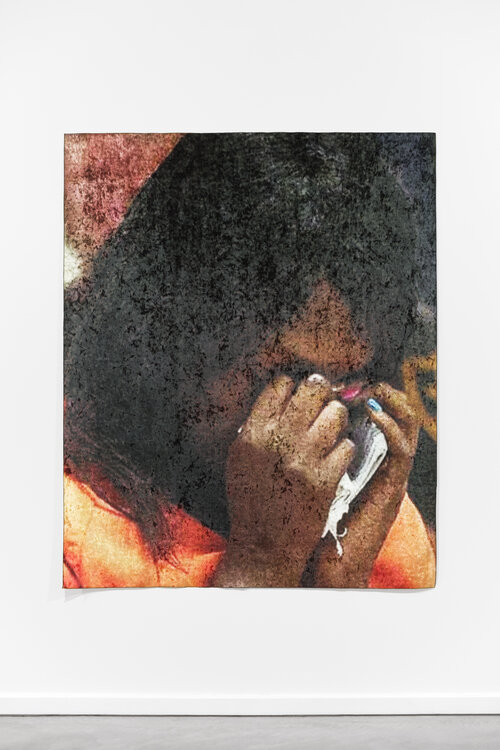

Léa Belooussovitch, Perp Walk (Handkerchief) detail (2019)

Photographic print on marbled velvet

Photo © Gilles Ribero

Photographic print on marbled velvet

Photo © Gilles Ribero

How would you define the notion of resistance in the context of your practice? Would you say this is a concept that applies to your work? What are you resisting?

This is not necessarily the first notion that I think of when I create my pieces, but it is true that in my series of drawings on felt we could speak of a resistance to disappearance, to trauma, to the image-reine... in my other works, perhaps we can talk about resistance to injustice, resistance to the image-as-proof, resistance to violence in general.

Léa Belooussovitch, Ejere, Ethiopie, 10 mars 2019 (Ethiopian airlines 302) (2020)

Drawings with colour pencils on felt

Photo ©Gilles Ribero

How do care and resistance intersect within your projects? Is caring a form of resistance? Is resisting a way to take care?

As an image producer, I try through my works to face the monster Image: to apprehend it and probe it in its worst aspects, as one learns to know their enemy well. In opposition to the cruelty the Image can carry within itself, and its most incisive, intransigent, accusatory, dramatic sides, I put in place strategies of gentleness, repair, resilience, anonymization, enhancement of misplaced vulnerability; in a sense we can say this is a form of resistant reaction, a humane wish to take care of the irreparable.

![]()

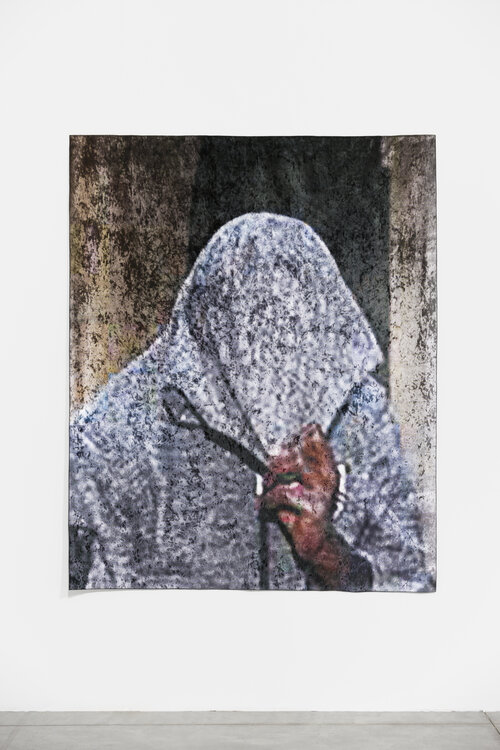

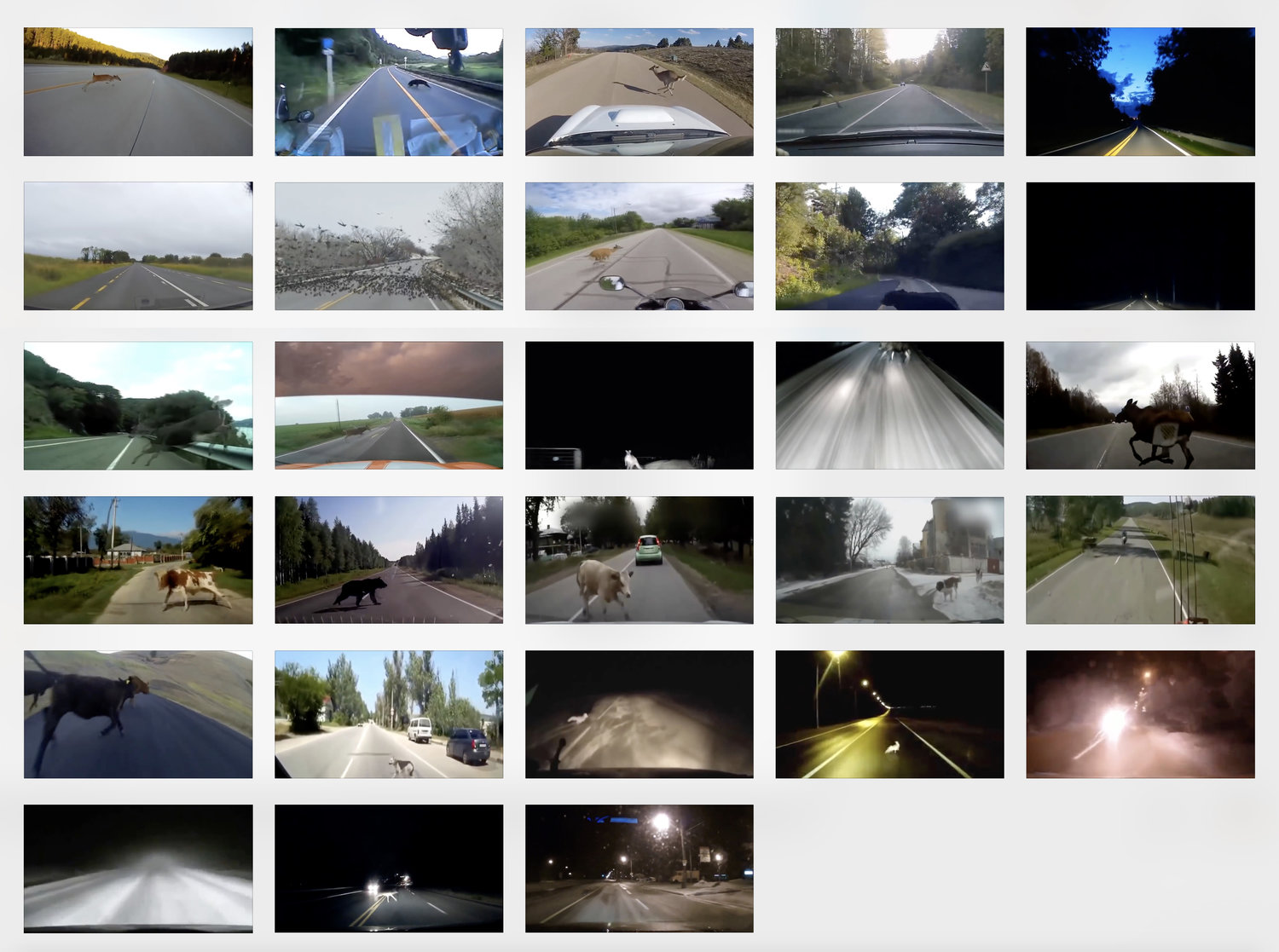

Léa Belooussovitch, The Blue Wall of Silence - Anonymous Witnesses (2019)

Serie of 24 images.

The original images are screenshots taken from amatorial videos documenting instances of police brutality, the victims have been digitally erased.

What is for you the role of images and their power, or their limits, in this process?

Images are limitless, I think. It is the man who, through censorship, editorial choice, restriction, computer tools, constrains it. We see it today with the beginnings of A.I: very soon, it will be equally difficult to prove that an image is true as to prove that it is false: I find this issue fascinating because at its core it is an issue of Truth, in the philosophical sense of the term. If we don't constrain the image, the image will devour us completely, the monster we have created will be uncontrollable and it is not impossible to imagine democracies crumble in the aftermath, for example, or entire populations take refuge into different versions of reality. The image can end up destroying the notion of truth and I find that very dangerous. I think it's a monster that needs to be contained so it doesn't devour everything in its path.

Léa Belooussovitch, The Blue Wall of Silence - Anonymous Witnesses (2019)

Serie of 24 images.

The original images are screenshots taken from amatorial videos documenting instances of police brutality, the victims have been digitally erased.

Is it possible to resist images through images?

I think you can twist them, manipulate them, question them, by touching them directly. For me, images are matter: a material that can be transformed, modeled, drawn, used, retouched, cut, printed, projected, etc. It is an immaterial material which is not structured like a language, however, it is through them that we communicate, and we have yet to learn how to read them, how to "speak image". Images are light, are pixels, are infinitely prolific, they are floating and everywhere around us, like particles. What is paradoxical is that without men, the Image would not exist.

The animal instead is free from this yoke.

![]()

Léa Belooussovitch, Jodhpur, Inde, 23 mai 2018 (2019)

Triptyc, Drawings with colour pencils on felt

Photos © Gilles Ribero

Is the violence of the gestures you employ (rubbing the pencil on felt, cropping, erasing)a response to the violence of the original images you manipulate? Do you think these gestures can paradoxically offer a form of reparation?

It’s a form of reaction, yes, a little revenge towards the Image. I felt a need to remove certain intolerable elements (as I did in The Methods, Blue Wall of Silence) in order to transform the very meaning of the image, to deceive it, to amputate it. By changing its meaning, the image says something different, something more vulnerable; in a way it is as if these gestures applied to the image serve as a means to change its meaning. Rubbing the pencil on the felt may seem a little aggressive, but at the same time it’s also an emphatic and a purging action: it’s like injecting the violence of the trauma directly into the fibers, and discard it there to be able to step into resilience.

Léa Belooussovitch, Jodhpur, Inde, 23 mai 2018 (2019)

Triptyc, Drawings with colour pencils on felt

Photos © Gilles Ribero

Léa Belooussovitch, Les Méthodes (2015)

A series investigating how acts of violence are administered: the original photographs depicts executions in countries that still apply the death penalty in public.

The executioners are present in the photographs while those accused have been removed.

A series investigating how acts of violence are administered: the original photographs depicts executions in countries that still apply the death penalty in public.

The executioners are present in the photographs while those accused have been removed.

Six questions sur le soin et la résistance: Léa Belooussovitch

Comment définiriez-vous la notion de soin dans le contexte de votre pratique?

Dans ma pratique, je dirais que la notion de soin pourrait s’apparenter à la fois aux matériaux, aux sujets et aux gestes plastiques. Le textile est très présent, en tant que support de réception de sources textuelles ou d’images : souvent ce sont des textiles non tissés (feutre, serpillières, torchons à usage unique..) qui ont de fortes capacités d’absorption, à la fois de la matière mais aussi sonore. Je les vois un peu comme des pansements, des buvards qui s’imprègnent d’une vulnérabilité ou d’une blessure.

Par des actes aussi de recadrage dans des images existantes, en éliminant des zones de l’image, c’est comme si l’image en était épurée et donc « guérie »; souvent dans mes oeuvres, on ne voit rien de directement violent, la violence se situe hors champ, dans un texte ou dans le contenu, en ce sens c’est aussi une forme de soin visuel.

Les sujets que j’aborde, comme par exemple les dernières volontés de condamnés à mort, les femmes de criminels accusées, ou les animaux malmenés par les hommes, sont des sujets toujours empreints d’une humanité bafouée, une innocence, et leur donner la place centrale d’une oeuvre est une manière de prendre soin d’eux.

Léa Belooussovitch, Perp Walk (Hood) (2019)

Impression photo sur velours marbré

Photo © Gilles Ribero

Comment définirais-tu la notion de résistance dans le cadre de ta pratique ? Dirais-tu que c’est un concept qui s'applique à tes travaux ? Contre quoi tu résistes?

Ce n’est pas forcément la première notion à laquelle je pense lorsque je crée les oeuvres, mais c’est vrai que dans mes dessins sur feutre on pourrait parler d’une résistance à la disparition, au traumatisme, à l’image-reine.. dans mes autres pièces, peut-être une résistance à l’injustice, à l’image-preuve, à la violence de manière générale.

![]()

Léa Belooussovitch, Ejere, Ethiopie, 10 mars 2019 (Ethiopian airlines 302) (2020)

Dessins aux crayons de couleur sur feutre

Photo ©Gilles Ribero

Quelle serait pour toi l’articulation entre soin et résistance et quelle forme cela prend dans tes projets ? Prendre soin est-il une forme de résistance ? Résister est-il une façon de prendre soin?

Face au monstre Image et en tant que productrice d’images, je dirais que je tente par mes oeuvres de lui faire face, de l’appréhender et le sonder sous ses pires aspects, comme on apprend à bien connaître son ennemi. En opposition au cruel, au côté incisif, immédiat, intransigeant, accusateur, dramatique que peut porter en elle l’Image, les stratégies que je mets en place sont plutôt de l’ordre de la douceur, de la réparation, résilience, l'anonymisation, mise en valeur de la vulnérabilité qui a pu être égarée; en ce sens on peut dire que c’est une forme de réaction résistante, dans un axe d’humanité et de prendre soin de l’irréparable.

Léa Belooussovitch, Ejere, Ethiopie, 10 mars 2019 (Ethiopian airlines 302) (2020)

Dessins aux crayons de couleur sur feutre

Photo ©Gilles Ribero

Léa Belooussovitch, The Blind side (2019)

Quel est pour toi le rôle de l’image et leur pouvoir - ou leurs limites - dans ce processus ?

Les images sont sans limites, je pense. C’est l’homme qui par la censure, le choix éditorial, la restriction, l’outil informatique, la contraint. On le voit aujourd’hui avec les prémices de l’A.I : très bientôt, il sera aussi difficile de prouver qu’une image est vraie que de prouver qu’elle est fausse : je trouve cette question fascinante car elle met au coeur le problème de la Vérité, au sens philosophique du terme. Si l’on ne contraint pas l’image, l’image va nous dévorer complètement, le monstre que nous avons crée sera alors incontrôlable et par exemple, il n’est pas impossible de voir s’écrouler les démocraties, de voir des populations s’engouffrer dans des versions différentes de la réalité; l’image peut finir par anéantir la notion de vérité et je trouve cela très dangereux. Je pense que c’est un monstre qui doit être contenu afin qu’il ne dévore pas tout sur son passage.

Est-ce possible de résister aux images par le biais des images elles-même ?

Je pense que l’on peut la tordre, la manipuler, la questionner, en la touchant directement. Pour moi les images constituent une matière. Une matière qui peut être transformée, modelée, dessinée, utilisée, retouchée, coupée, imprimée, projetée… c’est une matière immatérielle, qui n’est pas structurée comme un langage. Pourtant, c’est par elles que nous communiquons, et nous n’avons pas appris à les lire, à "parler image". Les images sont lumière, sont pixels, sont prolifiques à l’infini, elle sont flottantes et partout autour de nous, comme des particules. Ce qui est paradoxal, c’est que sans l’homme, l’Image n’existerait pas. L’animal lui, est libre de ce joug.

![]()

Léa Belooussovitch, The Blue Wall of Silence - Anonymous Witnesses (2019)

Serie of 24 images. The original images are screenshots taken from amatorial videos documenting instances of police brutality, the victims have been digitally erased.

La violence des gestes (frotter le crayon sur le feutre, recadrer, effacer) est-elle une réponse à la violence des images à partir desquelles tu travailles ? Comment expliquerais-tu que ces gestes offrent paradoxalement une forme de réparation ?

C’est une forme de réaction, oui, ou une petite vengeance envers l'Image. Une sorte de besoin d’enlever certains éléments intolérables (Les Méthodes ou Blue Wall of Silence par exemple) afin de transformer la signification même de l’image, de la tromper, de l’amputer. En changeant son sens, elle dit autre chose de plus vulnérable, en quelque sorte c’est comme si ces gestes appliqués aux images servaient de moyen pour changer leur sens. En frottant le crayon sur le feutre, c’est un peu agressif mais en même temps emphatique et purgatoire : c’est comme injecter par le geste la violence du traumatisme pour s’en débarrasser à l’intérieur des fibres, et entrer dans la résilience.

Léa Belooussovitch, The Blue Wall of Silence - Anonymous Witnesses (2019)

Serie of 24 images. The original images are screenshots taken from amatorial videos documenting instances of police brutality, the victims have been digitally erased.

Léa Belooussovitch, Les Méthodes (2015)

A series investigating how acts of violence are administered: the original photographs depicts executions in countries that still apply the death penalty in public.

The executioners are present in the photographs while those accused have been removed.

The executioners are present in the photographs while those accused have been removed.

´Behind every image is a relationship´

Note from an interview with Eva Giolo, april 2024

︎ https://elephy.org/profiles/eva-giolo

Léa Belooussovitch: The Hunt (2016)

︎ Read about this work on the artist´s website